The Case for App Patronage

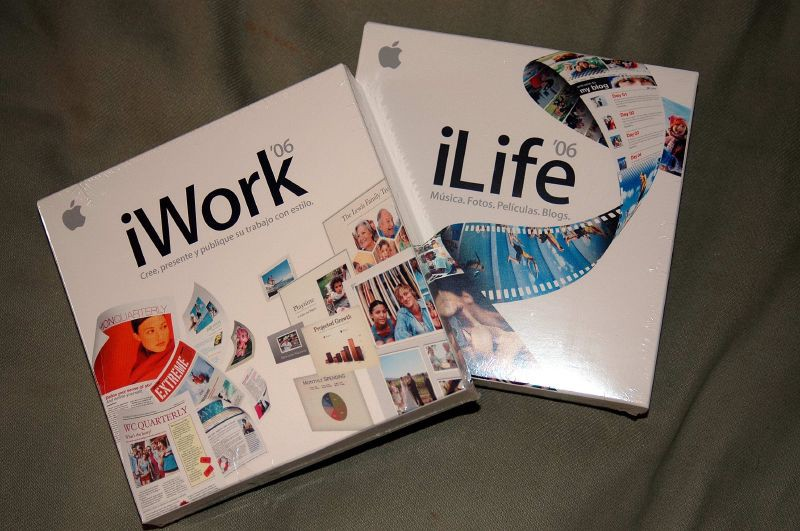

The boxed software model is dead.

It’s hard to be the Apps [Person]. Long build-outs, fierce competition, and the constant allure of more lucrative opportunities make the bootstrapped app business a daunting affair. A new approach is needed to make apps-as-a-business viable. Now is the right time to make the change.

The boxed software model is dead.

Selling an app (or unlocking premium features) with a one-time purchase is flawed. It became popular in the era of boxed software where developers could release a new version every year or two and capture more revenue from happy users. The app store has destroyed that model. Some developers have made compromises or pulled out from the app store altogether. As Phil Schiller recently pointed out: Apple considers this to be a model of the past and encourages developers to move out of the shrink-wrapped software era. Moving on is easier said than done when in-app purchase based models don’t command the same price points or margins.

Supporting and developing an app is a continuous process.

Customers expect a certain level of support, bug fixes, and customer service but these things cost the developer time and money. Without the potential of the customer buying a pricey upgrade (that the box software model provided), what incentive does the developer have to support their work? This lack of upside contributes to the abundance of abandonware and low-quality software on the app store. Developers lack the incentive to continue to develop and support their software. Under the one-time purchase model, developers are better off launching, making a splash, and moving on. A new model is needed to fix this misalignment.

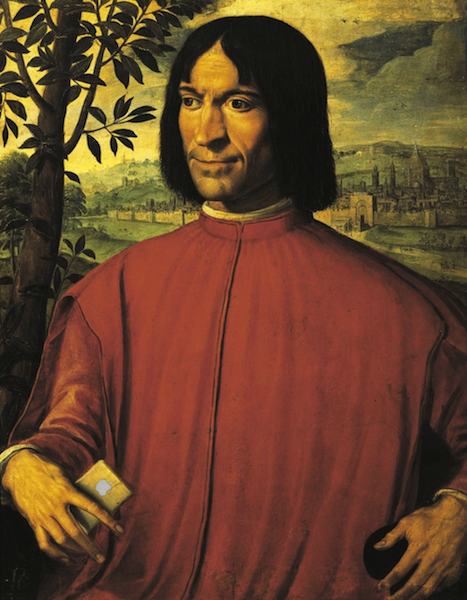

A renaissance of patronage

Artistic patronage was commonly used across the renaissance world. Wealthy “patrons” would support artists financially and socially, allowing them to create art that would proclaim the glory of God (and more often than not, that of the patron). The some of the most famous of these patrons were the Medici family of Florence. The artists they patronized included the likes of Raphael and Michelangelo, and their contributions to the arts made Florence the cultural center of the world. However, not everyone has access to a wealthy family of merchants.

Every user a patron

App patronage is renaissance patronage on a democratic scale. It can be achieved technically with auto-renewing subscriptions (and possibly other in-app purchases). Implementation can be direct, as Marco does in Overcast or less obviously patronage like many self-improvement apps such as Elevate. Subscriptions establish a patronage relationship between the developer and their users, restoring the incentives for continued support that were destroyed by the app store.

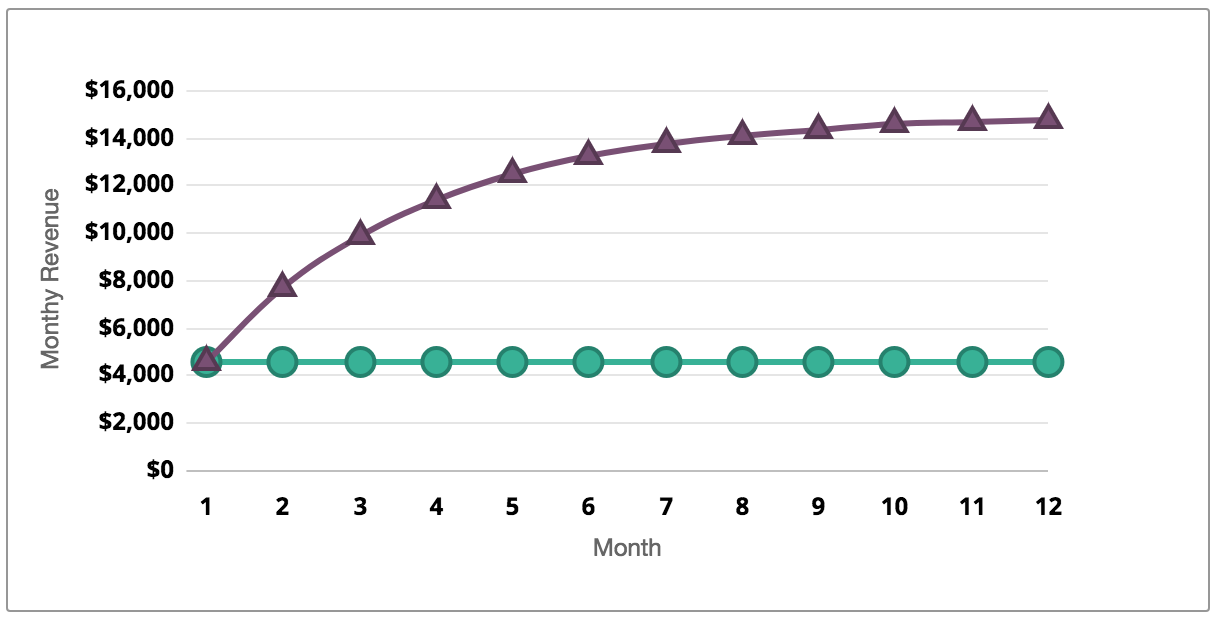

Make less money more often

Recurring revenue is more lucrative for developers than one-time purchases. It’s difficult to establish a direct comparison of an app with one-time vs. recurring purchases, but all the anecdotal evidence I’ve encountered points to recurring as the clear winner. The general success of software as a service models, especially in business-to-business apps, has been attributed to the strength of building a recurring revenue base.

Alignment

App patronage provides much-needed alignment between developers and customers. If a developer’s revenue stream relies on the continued satisfaction of their customer base, it gives the developer a direct incentive to prioritize things like updates and customer support, often neglected aspects of the app lifecycle. The developer is incentivized to make a few people very happy instead of falling into the trap of making a lot of people only somewhat happy. This smaller group of very happy people help the developer to build a community, as we see in services like Patreon or Gumroad. The developer can leverage this community.

This week in James-is-not-writing-a-game – new camera modes, a speedometer, and persistent high scores.

Stability

Having a mature, stable community of customers allows developers to take more risks and create apps and functionality that otherwise wouldn’t be viable. Once a developer has cultivated a core base of enthusiastic patrons, their enthusiasm is transferable to new features or other products. Products and features that may not have been possible otherwise. A great example of this is Pcalc developer James Thomson. This past year he added AR features and a small game to the Pcalc about screen. A purely “for fun” feature addition that, without an active, supportive community, might not have been possible. Apple and Google are even making changes to their platform policies to encourage the building of long-term customer bases.

In 2016 Apple and Google announced that they would be reducing their fees for recurring revenue after a customer has been retained for one year. Apple also recently released introductory pricing, giving developers new flexibility in their subscriptions plans. Meanwhile Apple has been singing the praises of their soaring recurring revenue growth for the last handful of quarters. All of this has provided a clear signal that they want more developers using the recurring revenue model. If it helps the App Store and Play Store to make more money while reducing the shovel-ware issue then it’s a win-win for them. It tells developers that their definition of an acceptable use of auto-renewing subscriptions is widening and that it is unlikely to narrow soon.

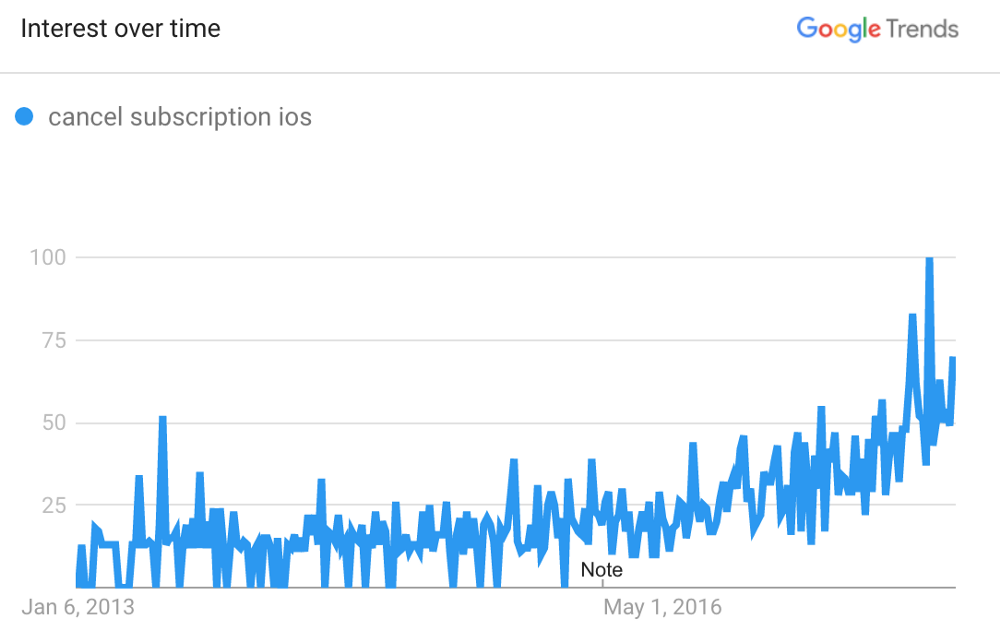

Subscription fatigue is a real thing.

With all the fawning over recurring revenue, it’s easy to overlook some of the associated drawbacks associated. On iOS canceling a subscription is entirely too hard. It is unlikely that this is by accident. If Apple makes canceling a subscription simpler, churn rates will go up. However, doing nothing will contribute to the continued rise of subscription fatigue: the resistance to and rejection of using auto-renewing subscriptions. In the long term, this will hurt the ecosystem and erode consumer trust in Apple and developers. Google, for what it’s worth, does a better job of letting people manage their subscriptions, but both companies have a long way to go to solve this problem.

Implementation details

Auto-renewing subscriptions still require a lengthy build-out to implement correctly. You need a backend, an in-depth understanding of the API, and at least a month of developer time. Tools like RevenueCat (made by some brilliant and handsome people) help bridge the gap for developers. I believe that the benefits of recurring app patronage should be available to all developers, regardless of their resources.

The arc of history is long but it bends towards app patronage.

A small team can build great software, but if they don’t monetize it well, it will fail and fade away, ending up buried in New Mexico somewhere. Changing consumer attitudes, support from the platform makers, and improved tooling make 2018 the year to move to a sustainable model for app development. The time is now for app patronage to become the de facto revenue model for quality apps.

You might also like

- Blog post

The complete guide to SKAdNetwork for subscription apps

Understanding Apple's privacy-first attribution

- Blog post

“A big market is great only if you can take a substantial share of it” — Patrick Falzon, The App Shop

On the podcast: estimating the revenue potential of an app, crafting an exit strategy, and why LTV is such a terrible metric.

- Blog post

Effective testing strategies for low-traffic apps

Is A/B testing off the table? Let’s rethink experimentation.